Americans' Top Concerns Reflect Both Common Ground and Partisan Splits: Economy Unites, but Policy and Politics Divide

Hwayong Shin, Weidenbaum Center Postdoctoral Fellow in Survey Research

November 6, 2025

Over the past two years, Americans have lived through several political shocks—both at home and abroad. In 2023, the removal of House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, the Supreme Court’s reversal on affirmative action, the outbreak of the Israel–Hamas war, and Donald Trump’s multiple indictments shook the political landscape. In 2024, Americans faced a series of events surrounding the presidential election—Trump’s conviction on felony charges, the Supreme Court’s subsequent ruling granting him presidential immunity, Joe Biden’s faltering debate performance that led to his withdrawal and Kamala Harris’s nomination, and Trump’s return to the White House. Since the new administration took office in January 2025, policy shifts across a wide range of domains—including tariffs, education, immigration, and foreign affairs—have given Americans a lot to think about.

With so many options, which issues do Americans think are most important? Data from the Weidenbaum Center Survey (WCS) between October 2023 and May 2025 offer key insights. The WCS is a nationally representative survey, including an oversample of African Americans, fielded by YouGov three times each year by faculty affiliated with the Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy at Washington University in St. Louis. The rich data reveal notable trends in how Americans think about the nation’s most important problem.

Across time and party lines, the economy and inflation topped Americans’ concerns. Yet Democrats and Republicans differed in which policy areas—such as climate change, immigration, and gun control—and which issues of governance—like democracy, polarization, and party leadership—they viewed as the nation’s most important problems.

What is the Most Important Problem Facing the Country?

Since 2023, 10,492 unique respondents to the WCS have answered the open-ended question, “What do you think is the single most important problem facing the country?” Unlike closed-ended questions that ask respondents to assess the relative importance of a pre-specified set of topics (e.g., Gallup 2024; Pew Research 2025), the WCS did not prompt any specific topics and allowed respondents to provide answers in their own words. Open-ended responses “provide a direct view into a respondent’s own thinking” (Roberts et al. 2014, p.1065), unconstrained by the researchers’ preconceptions.

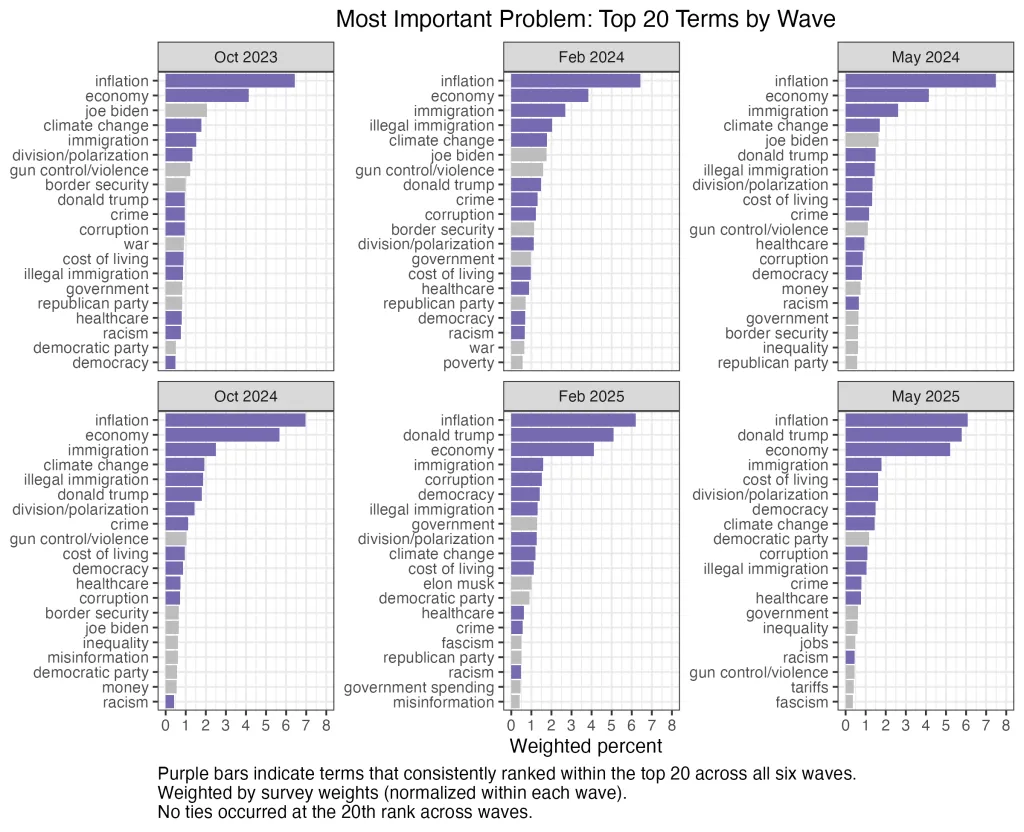

Across all six waves, thirteen terms consistently ranked within the top 20 most-mentioned problems—shown as purple bars in the figure below—revealing three broad themes: 1) the economy (cost of living, economy, inflation), 2) public policies (climate change, crime, healthcare, immigration, illegal immigration), and 3) politics and governance (corruption, democracy, division/polarization, Donald Trump, racism). Although the overall percentages of Americans reporting each term as the Most Important Problem are low, they reflect a fine-grained measure, capturing only responses that used exactly matching words (see methodological details below). In contrast, other analyses, such as Gallup’s (2024) reporting of open-ended responses, combine responses into broader categories, which can yield higher percentages of Americans considering a broad issue to be important.

Economic concerns consistently stood out as the foremost issue across all waves. In every wave, “inflation” ranked first, with 6.1–7.5% of Americans naming it as the single most important problem facing the country. This pattern is consistent with previous research documenting the economy’s central role in shaping public concern and in citizens’ evaluations of government performance and voting decisions (Lewis-Beck & Stegmaier 2019; Roberts et al. 2014). “Economy” ranked second or third, cited by 3.8–5.7% of respondents, while “cost of living” became increasingly salient, rising from the 13th to 5th place by May 2025. Inflation, federal budget deficits, and slowing growth between 2023 and 20245—as reflected in GDP trends, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), and rising food prices (Congressional Budget Office 2024; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2025; U.S. Department of the Treasury 2024)—likely have kept the economy and inflation salient in many American’s minds.

A range of policy domains—including climate change, crime, healthcare, and immigration—was also salient in many Americans minds, consistently ranking within the top 20 mentioned terms. “Immigration” ranked 3rd–5th (1.5–2.7%), while “illegal immigration” appeared separately, ranking 4th–11th (0.9–2%). When combined, “immigration” emerges as the most salient policy issue overall, aside from the economy. “Climate change” ranked 4th in October 2023 but showed a slight downward trend (1.2–1.9%), though it remained in the top 10 throughout. “Crime” and “healthcare” consistently appeared in the top 20 but were each named by only about 1% of respondents. These patterns align with recent research on partisan divisions surrounding immigration, environmental, crime, and healthcare policies (Marietta & Barker 2019; Patashnik 2023).

Politics and governance also emerged as a major theme, as reflected in five of the thirteen consistently mentioned terms. Two that showed a clear upward trend were “Donald Trump”—rising from 9th (1 %) in October 2023 to 2nd (5.8 %) in May 2025—and “democracy—rising from 20th (0.5 %) to 7th (1.5 %) over the same period—reflecting growing public concern about leadership and the quality of democratic governance. “Corruption” (0.7–1.5%) “division/polarization” (1.1–1.6%), “racism” (0.5–0.8%) also consistently ranked within the top 20, indicating sustained public concern over corruption and social division. These trends resonate with prior research showing that unemployment and inflation affect government popularity (Berlemann & Enkelmann 2014), that democratic backsliding has become as a core concern in U.S. politics (Druckman et al. 2024), and that corruption, racism, and partisan divisions remain enduring challenges with important consequences for democratic accountability (Cramer 2020; De Vries & Solaz 2017; McConnell et al. 2017; Iyengar et al. 2019).

Beyond these recurring issues, during the Biden presidency (October 2023; February 2024, and May 2024), the top 20 terms also included “Joe Biden,” “gun control/violence,” “war,” and “republican party.” Since the 2024 presidential election period and the onset of Trump’s second administration (October 2024; February and May 2025), new terms entered the top 20, such as “misinformation,” “Elon Musk,” “fascism,” “tariffs,” and “Democratic Party.” These trends reflect how recent changes in the political landscape have shaped Americans’ perceptions of the nation’s most important problems.

A notable observation is the sheer variation in how Americans perceive “the single most important problem facing the nation.” Even the most frequently mentioned term—“inflation”—was cited by only 6.1–7.5% of respondents. Although policy issues such as “climate change,” “immigration,” “crime,” and “healthcare” consistently ranked among the top 20 mentioned terms, each was named by only about 1–3% of respondents. This dispersion likely reflects what Zaller (1992) described as the “top of the head” nature of survey responses: individuals base their answer on the considerations that are “readily accessible” when prompted to assess public affairs or policies (p.49). The fact that no single issue was mentioned by a large majority underscores the diversity of considerations that come to mind for Americans, and more broadly, the pluralism of the public’s aspirations and concerns.

Bipartisan Concerns about the Economy, Partisan Split on Public Policy and Governance

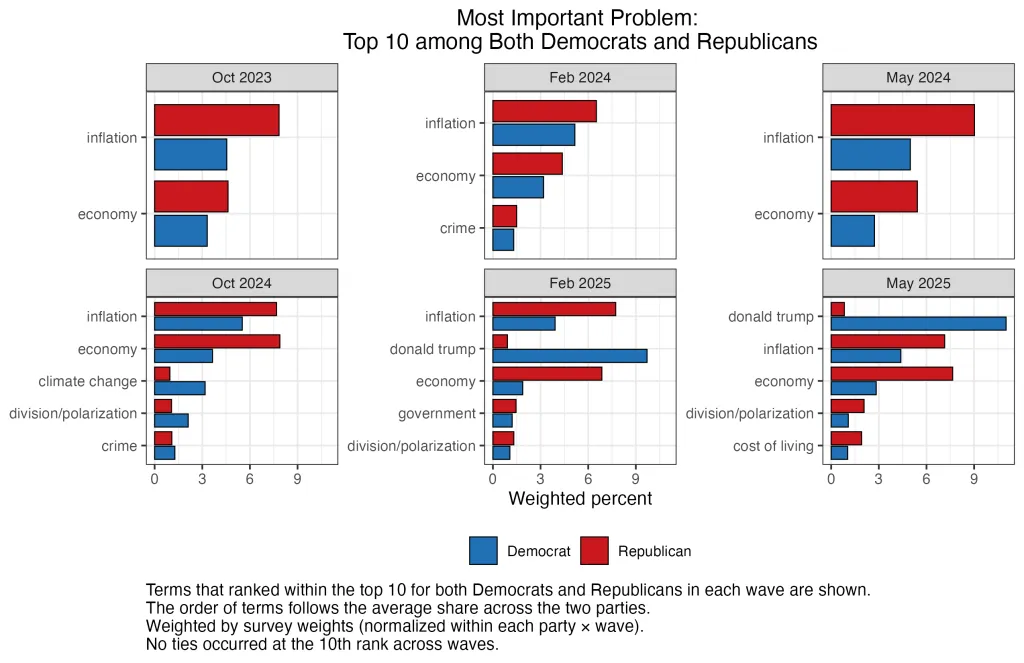

When are Democrats and Republicans similar or different in their perceptions of the most important problem facing the United States? To address this question, the most frequently mentioned top 10 terms were identified for each partisan group in each wave. The results indicate bipartisan salience of the economy but divergent priorities on public policy and governance.

The figure below displays the terms that ranked within the top 10 among both Democrats and Republicans in each wave. “Inflation” and “economy” were top bipartisan concerns across all six waves, while “cost of living” also emerged as a shared concern in May 2025. Regarding public policy, only a few issues made it into the top 10 for both groups: “crime” (February 2024, October 2024) and “climate change” (October 2024). Starting in late 2024 and continuing into 2025, beyond the economy, bipartisan concerns have increasingly centered on politics and governance, with “division/polarization,” “Donald Trump,” and “government” ranking within the top 10 across party lines.

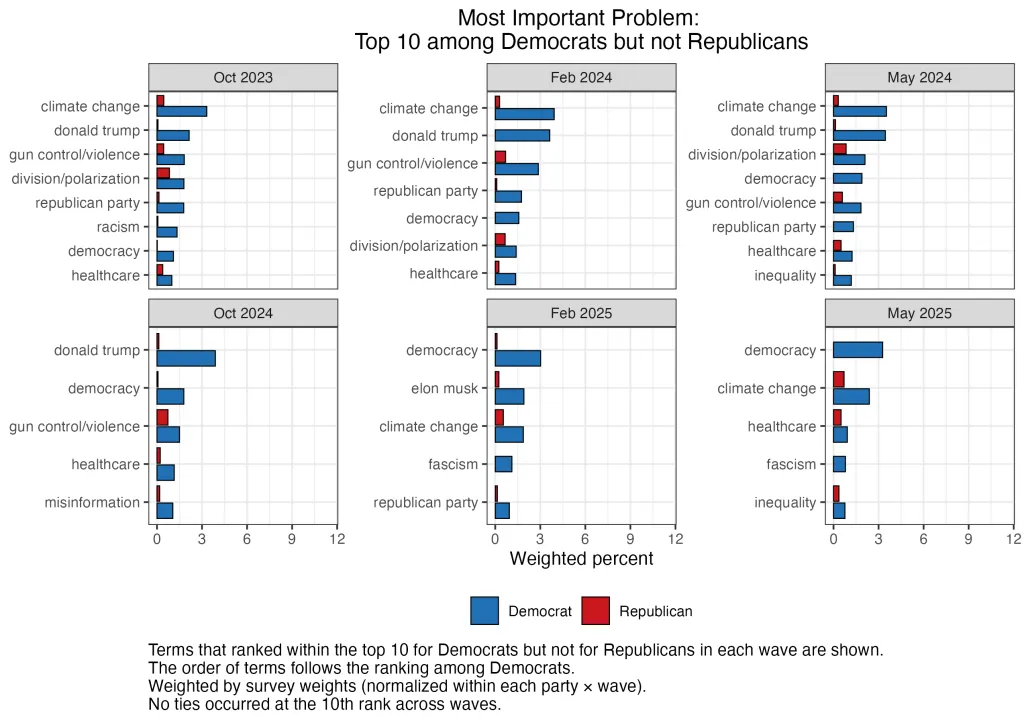

Partisan splits were more pronounced on public policies and governance. The figure below illustrates the issues that ranked within the top 10 among Democrats but not Republicans. Among Democrats, policy issues such as “climate change,” “healthcare,” and “gun control/violence” have consistently been salient. On politics and governance, “democracy,” “Donald Trump,” and “racism” consistently emerge as top concerns, along with “Republican Party.” Terms such as “misinformation,” “fascism,” “Elon Musk,” and “inequality” also appeared in later waves. On these issues, the percentage of Republicans mentioning them was minimal, indicating that these topics were salient among Democrats but less so among Republicans.

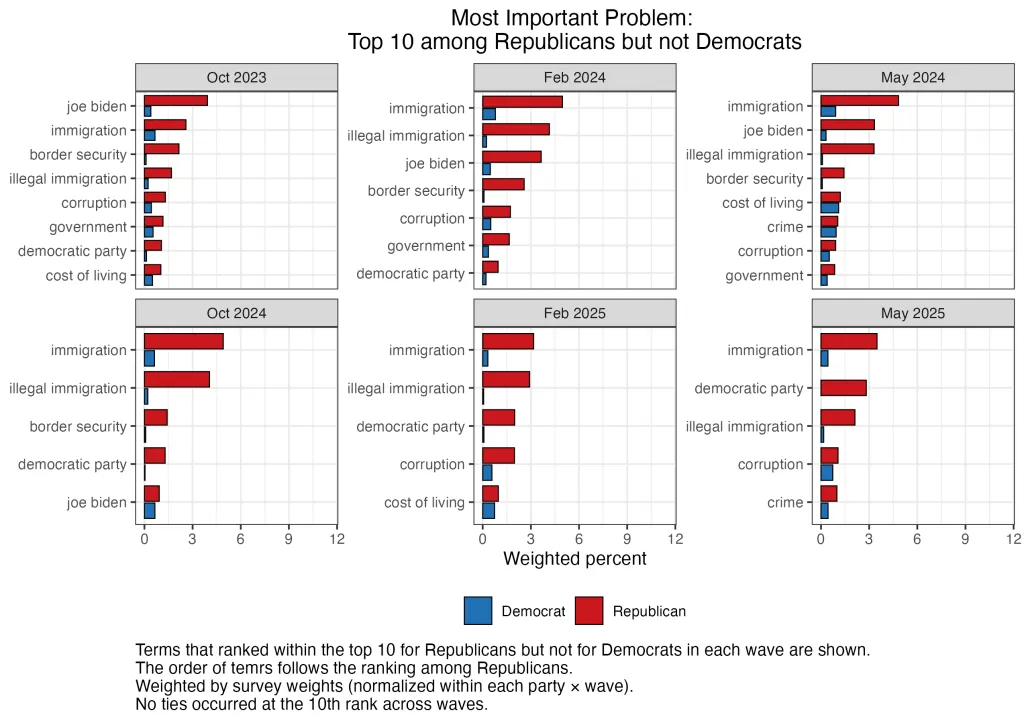

In contrast, Republicans’ top concerns reflected a different set of policy and governance priorities. The figure below, which displays the term that ranked within the top 10 among Republicans but not Democrats, reveals the set of issues that are more salient to Republicans. On public policy, immigration stood out: “immigration,” “illegal immigration,” and “border security” consistently ranked high, with “crime” also appearing in the top 10 in two waves. On politics and governance, “corruption” and “government” were recurring concerns across waves, while “Joe Biden” and the “Democratic Party” were also often identified as problems facing the country. On these topics, the share of Democrats mentioning them was minimal.

Taken together, these bipartisan and party-specific top terms illustrate where Democrats and Republicans converge and diverge on what they perceive as the nation’s most pressing problems. While both groups consistently emphasize the economy, they diverged on the policy and governance fronts. On public policy, climate change and gun policy were more salient among Democrats, whereas immigration and border security were more salient among Republicans. On governance, Democrats were more concerned about democracy and racism, whereas Republicans were more concerned about corruption. Both groups frequently identified the opposing party or leader as a problem, echoing research on growing partisan hostility (Iyengar & Westwood 2015).

While the broad contours of partisan convergence and divergence remain largely stable, the relative prominence of specific issues has evolved over time. The figure below traces the share of mentions over time for the terms that consistently ranked within the top 10 among Democrats and Republicans, respectively.

On the economy, while “inflation” and “economy” remained consistent top 10 concerns for both groups, substantially larger shares of Republicans (inflation: 6.5–9.0%; economy: 4.4–7.9%) than Democrats (inflation: 3.9–5.5%; economy: 1.9–3.6%) identified these as the nation’s most important problems. On public policy, “immigration” (2.6–5%) and “illegal immigration” (1.7–4.2%) consistently ranked high among Republicans, whereas “climate change” (1.9–3.9%) was an enduring concern among Democrats. The concerns around politics and governance were more prominent among Democrats than Republicans. “Division/polarization” (1.1–2.1%) consistently ranked within the top 10 among Democrats, who were consistently—and increasingly—concerned about “democracy” (rising from 1.1% in 2023 to 3.3% in 2025) and “Donald Trump” (from 2.1% to 11%).

These over-time trends reinforce that the economy remains a salient bipartisan concern, while Democrats and Republicans emphasize different public policies—consistent with prior research showing that Republicans tend to be more negative toward immigration (Ollerenshaw & Jardina 2023), and that Democrats tend to be more supportive of climate mitigation (Egan & Mullin 2023) and gun control (Ryan et al. 2020). The trends further reflect growing partisan polarization, where Democrats and Republicans increasingly attribute the nation’s problem to the opposing party (Levendusky et al. 2024).

Independents at a Middle Ground between Democrats and Republicans

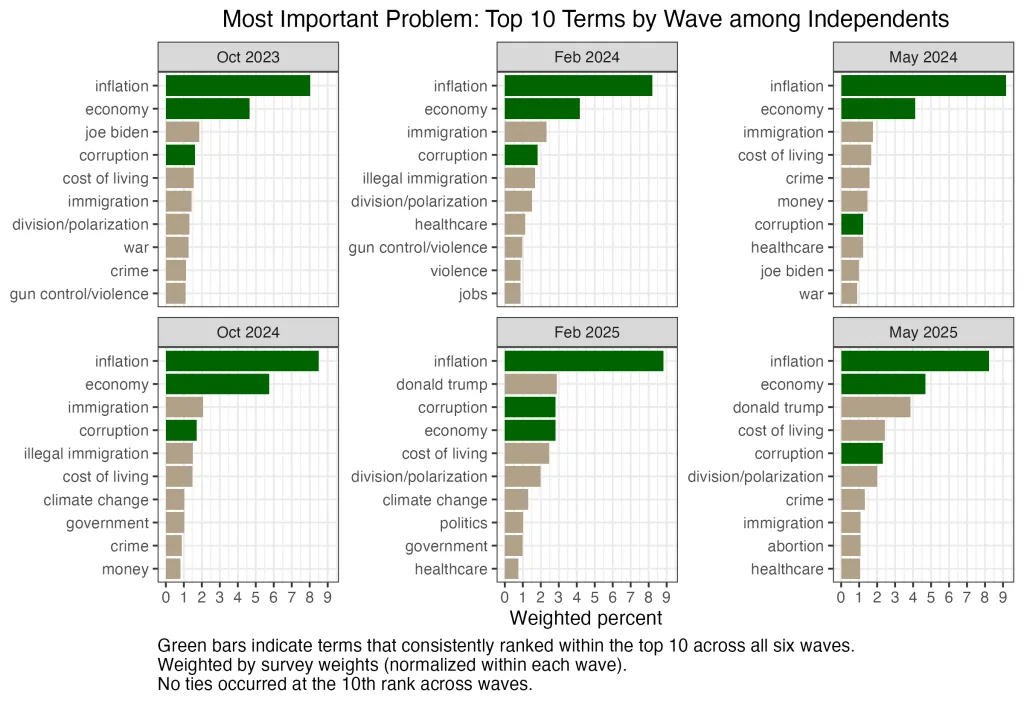

Independents—those who do not align with either major party—play an important role in U.S. politics and hold distinct political views (Bankert 2022; Klar & Krupnikov 2016; Siev et al. 2024). Political science research often focuses on pure independents and treats partisan leaners as partisans, as leaners tend to resemble partisans in their political attitudes and behavior (Petrocik 2009). In the current analysis, Independents refer to pure independents—individuals without partisan leanings—who constitute roughly 7–8% of Americans in recent years (Pew Research Center 2025). The figure below shows the terms that Independents most frequently mentioned in each wave, where green bars indicate those that consistently ranked within the top 10 across all six waves.

The issues that consistently ranked in the top 10 among Independents included economic concerns (“inflation,” “economy”) and politics and governance (“corruption”). Compared with partisans, Independents shared economic concerns with both Democrats and Republicans and shared concerns about corruption—pertaining to the integrity of government—with Republicans. Unlike partisans, however, the top 10 mentioned terms among Independents did not include specific political parties (e.g., Democratic or Republican Party).

Beyond these issues, Independents often pointed to the country’s incumbent leadership as a problem: “Joe Biden” appeared in the top 10 in October 2023 and May 2024, while “Donald Trump” appeared in February and May 2025. Other frequently mentioned terms included policy issues such as “crime,” “climate change,” “healthcare,” “immigration” and “illegal immigration,” as well as governance-related issues such as “division/polarization.” The range of recurring concerns of Independents encompassed both the bipartisan and party-specific top concerns observed among Democrats and Republicans.

Overall, Independents’ concerns occupy a middle ground between those of Democrats and Republicans. Their enduring focus on economic issues and corruption, along with recurring concerns about public policies that cut across partisan divides, reflects both shared bipartisan concerns and cross-cutting priorities.

Bottom Line

The findings from the WCS, which spans 2023 through 2025, reinforce the enduring relevance of the phrase “It’s the economy, stupid” in Americans’ perceptions of the nation’s most important problem. These results are consistent with recent survey findings by Gallup (2024) and Pew Research (2025). The economy’s dominance was more pronounced in the WCS results compared to those other surveys that focused on a single year and relied on closed-ended responses or pre-specified categorizations of open-ended responses.

Yet beneath these bipartisan concerns about the economy lie deep partisan divides in policy priorities and in which political party is perceived as the nation’s problem—illustrating why “conflicting representations of public opinion are inescapable” (Fishkin 1995, p.4). The results indicate partisan splits in Americans’ top concerns surrounding public policy and governance, evoking a long-standing question in political science: Do leaders follow the voters, or do voters follow the leader? (e.g., Canes-Wrone 2005; Lenz 2012)

The divergent and partisan views on the nation’s most important problem suggest that the answer may be increasingly complex. In today’s political environment, the logic of the median voter theorem—which predicts that politicians move toward the median voter’s policy preference to maximize their chances of winning elections (Downs 1964)—appears increasingly less applicable. At the same time, partisan polarization has intensified, accompanied by growing hostility toward the other side (Abramowitz & Webster 2016; Mason 2015). Against this backdrop, Americans’ diverse perceptions of the nation’s most pressing problems paint a complex picture of how politicians can best pursue policies that meet the ideals of democratic responsiveness—and of the challenges citizens face in reconciling their hopes and expectations with the realities of governance.

Despite the challenges in evaluating citizens’ aspirations and concerns in the aggregate, over-time assessments of what comes to Americans’ minds when they think about the country’s problems may help illuminate which policy directions are most sustainable and conducive to the nation’s collective well-being. As V. O. Key, Jr. (1961) observed, “Unless mass views have some place in the shaping of policy, all the talk about democracy is nonsense” (p.7). This insight underscores how Americans’ evolving perceptions of the nation’s problems—and the reciprocal feedback between citizens and their representatives—continue to shape the foundations upon which public policy and democratic life rest.

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Taylor Carlson and Lukas Alexander for their constructive and helpful comments.

Bibliography

Abramowitz, A. I., & Webster, S. (2016). The rise of negative partisanship and the nationalization of U.S. elections in the 21st century. Electoral Studies, 41, 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2015.11.001

Bankert, A. (2022). Negative partisanship among Independents in the 2020 U.S. presidential elections. Electoral Studies, 78, 102490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2022.102490

Berlemann, M., & Enkelmann, S. (2014). The economic determinants of U.S. presidential approval: A survey. European Journal of Political Economy, 36, 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2014.06.005

Canes-Wrone, B. (2005). Who Leads Whom?: Presidents, Policy, and the Public. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/W/bo3624028.html

Congressional Budget Office. (2024, June 18). An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: 2024 to 2034 | Congressional Budget Office. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/60419

Cramer, K. (2020). Understanding the Role of Racism in Contemporary US Public Opinion. Annual Review of Political Science, 23(Volume 23, 2020), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-060418-042842

De Vries, C. E., & Solaz, H. (2017). The Electoral Consequences of Corruption. Annual Review of Political Science, 20(Volume 20, 2017), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-052715-111917

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York: Harper.

Druckman, J. N. (2024). How to study democratic backsliding. Political Psychology, 45(S1), 3–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12942

Egan, P. J., & Mullin, M. (2024). US Partisan Polarization on Climate Change: Can Stalemate Give Way to Opportunity? PS: Political Science & Politics, 57(1), 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096523000495

Fishkin, J. S. (1995). The Voice of the People: Public Opinion and Democracy. Yale University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt32bgmt

Gallup. (2024, March 29). Inflation, Immigration Rank Among Top U.S. Issue Concerns. Gallup.Com. https://news.gallup.com/poll/642887/inflation-immigration-rank-among-top-issue-concerns.aspx (Methodology: https://news.gallup.com/file/poll/642905/20240329IssueConcerns.pdf)

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22(Volume 22, 2019), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and Loathing across Party Lines: New Evidence on Group Polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690–707. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12152

Key, V. O. Jr. (1961). Public Opinion and American Democracy. New York: Knopf.

Klar, S., & Krupnikov, Y. (2016). Independent politics. Cambridge University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316471050

Lenz, G. S. (2012). Follow the Leader?: How Voters Respond to Politicians’ Policies and Performance. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/F/bo11644533.html

Levendusky, M., Ryan, J. B., Klar, S., & Krupnikov, Y. (2024). Partisan Animosity and Evaluations of Political Leaders. In Partisan Hostility and American Democracy: Explaining Political Divisions and When They Matter (pp. 96–121). University of Chicago Press. https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.7208/chicago/9780226833668-006/html

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Stegmaier, M. (2019). Economic Voting. In R. D. Congleton, B. Grofman, & S. Voigt (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public Choice, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190469733.013.12

Marietta, M., & Barker, D. C. (2019). One Nation, Two Realities: Dueling Facts in American Democracy. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190677176.001.0001

Mason, L. (2015). “I Disrespectfully Agree”: The Differential Effects of Partisan Sorting on Social and Issue Polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12089

McConnell, C., Margalit, Y., Malhotra, N., & Levendusky, M. (2018). The Economic Consequences of Partisanship in a Polarized Era. American Journal of Political Science, 62(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12330

Ollerenshaw, T., & Jardina, A. (2023). The Asymmetric Polarization of Immigration Opinion in the United States. Public Opinion Quarterly, 87(4), 1038–1053. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfad048

Patashnik, E. M. (2023). Countermobilization: Policy Feedback and Backlash in a Polarized Age. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo208176966.html

Pew Research Center. (2025a, February 20). Americans Continue to View Several Economic Issues as Top National Problems. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2025/02/20/americans-continue-to-view-several-economic-issues-as-top-national-problems/

Pew Research Center. (2025b, July 23). Party Affiliation Fact Sheet (NPORS). Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/fact-sheet/party-affiliation-fact-sheet-npors/

Petrocik, J. R. (2009). Measuring party support: Leaners are not independents. Electoral Studies, 28(4), 562-572. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261379409000511

Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., Tingley, D., Lucas, C., Leder-Luis, J., Gadarian, S. K., Albertson, B., & Rand, D. G. (2014). Structural Topic Models for Open-Ended Survey Responses. American Journal of Political Science, 58(4), 1064–1082. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12103

Ryan, J. B., Andrews, T. M., Goodwin, T., & Krupnikov, Y. (2022). When Trust Matters: The Case of Gun Control. Political Behavior, 44(2), 725–748. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09633-2

Siev, J. J., Rovenpor, D. R., & Petty, R. E. (2024). Independents, not partisans, are more likely to hold and express electoral preferences based in negativity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 110, 104538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2023.104538

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2025, January 24). Consumer Price Index: 2024 in review. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2025/consumer-price-index-2024-in-review.htm

U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2025, February 8). Economy Statement for the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee. U.S. Department of the Treasury. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sb0006

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511818691

Methods

The Weidenbaum Center Survey (WCS) was conducted by Washington University in St. Louis’s Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy through the survey firm YouGov on Oct 16–24, 2023 (Wave 1), Feb 15–26, 2024 (Wave 2), May 15–28, 2024 (Wave 3), Oct 15–23, 2024 (Wave 4), Feb 14–24, 2025 (Wave 5), May 15–26, 2025 (Wave 6). Among 10,492 unique respondents, some respondents participated in more than one wave of the WCS. For each wave, the analysis included the respondents who provided non-missing responses to the “most important problem” question: 3,278 (Wave 1), 3,043 (Wave 2), 3,182 (Wave 3), 3,247 (Wave 4), 3,229 (Wave 5), and 3,535 (Wave 6). Within each wave, the number of non-missing responses by partisanship was as follows: Democrats (D) = 1,674, Republicans (R) = 839, Independents (I) = 613 (Wave 1); D = 1,555, R = 814, I = 533 (Wave 2); D = 1,709, R = 791, I = 581 (Wave 3); D = 1,768, R = 886, I = 518 (Wave 4); D = 1,665, R = 878, I = 591 (Wave 5); and D = 1,838, R = 919, I = 692 (Wave 6). “Democrats” include individuals identifying as Strong Democrat, Not very strong Democrat, or Lean Democrat; “Republicans” include those identifying as Strong Republican, Not very strong Republican, or Lean Republican; and “Independents” refer to pure independents who identified as Independent without partisan leaning.

Using the open-ended responses to the question “What do you think is the single most important problem facing the country?”, the top-mentioned terms were extracted by first removing stop words, using the standard list in the R package tidytext, along with additional generic words (e.g., “country,” “single”, “people”, “issues”, “lack”, “threat”) that did not signal specific topics. Before tokenization, the multi-word expression “cost of living” was treated as a single token, given the frequent appearance of “cost” and “living” as separate unigrams. I then extracted unigrams and bigrams from open-ended responses. To prevent double counting, unigrams that appeared as components of any bigram mentioned by the same respondent within a given wave were dropped (e.g., if a response mentioned “illegal immigration,” it was not counted toward the unigrams “illegal” or “immigration”; if a response mentioned “immigration” alone, it was counted toward “immigration”). Because the WCS oversampled Black respondents, to avoid overrepresenting that group, counts of unigrams and bigrams were weighted by respondents’ survey weights to reflect population representativeness. By manually inspecting bigrams that were mentioned by at least 0.1% of all weighted responses across six waves (n = 55), synonymous expressions were collapsed to preserve conceptual consistency as shown below. In doing so, distinct substantive frames (e.g., immigration vs. illegal immigration, inflation vs. cost of living) were intentionally kept separate. Weighted frequencies were then summed by wave to identify the most frequently mentioned issues overall, over time, and by partisan groups.

Individuals:

- “joe biden,” “biden,” “biden administration” → joe biden

- “donald trump,” “trump,” “trump administration” → donald trump

- “elon musk,” “musk” → elon musk

- “president,” “white house,” “current administration,” “current president” →

joe biden for Waves 1–4; donald trump for Waves 5–6

Policies and issues:

- “illegal immigrants,” “illegal immigration,” “illegal aliens” → illegal immigration

- “healthcare,” “health care” → healthcare

- “climate,” “global warming,” “climate change” → climate change

- “political division,” “division,” “political divide,” “political polarization,” “polarization” → division/polarization

- “economy inflation,” “economic inflation,” “inflation,” “rising prices,” “inflation economy” → inflation

- “prices,” “food prices,” “cost of living” → cost of living

- “income inequality,” “economic inequality,” “inequality,” “wealth inequality” → inequality

- “political corruption,” “government corruption,” “corruption,” “corrupt government,” “corrupt politicians” → corruption

- “democrats,” “democratic party” → democratic party

- “republicans,” “republican party” → republican party

- “political parties,” “political party” → political parties

- “gun violence,” “gun control,” “guns,” “gun” → gun control/violence

- “rights,” “civil rights,” “human rights” → civil rights

- “fake news,” “misinformation” → misinformation

- “border security,” “southern border,” “border crisis,” “border,” “borders” → border security

- “abortion,” “abortion rights” → abortion

The weighted and unweighted frequencies were highly correlated across all waves (r = .91–.94). The two versions produced nearly identical frequencies, particularly among the most frequently mentioned issues (e.g., the top 20 terms). These strong correlations indicate that the relative ranking of issues remained substantively unchanged regardless of weighting. The weighted frequencies are presented to better reflect the composition of the U.S. population.

While the structural topic modeling (STM) is widely used to analyze open-ended responses (Roberts et al. 2014), it did not fit well with the “most important problem” question in the WCS. STM assumes “a model where each open-ended response is a mixture of topics,” in which each open-ended response “arises as a mixture over K topics” and “topic proportions can be correlated” (Roberts et al. 2014; p. 1067). Yet most open-ended responses in the WCS were very short—half of them were two words or fewer (median = 2), and 75% contained five words or fewer (75th percentile = 5). Because such short answers are less likely to contain multiple topics, the STM did not empirically extract coherent underlying themes. The extracted topics—regardless of whether the model assumed 10 or 20 topics—often contained words that did not indicate a coherent theme (e.g., loading “crime” and “healthcare” under the same topic). While STM can be useful for examining how covariates explain variations in underlying topics—as shown in Roberts et al. (2014)’s application—it showed limitations in identifying coherent topics in very brief open-ended responses. Therefore, the current analysis employs a method that systematically identifies the most frequently occurring unigrams and bigrams, while accounting for overlaps between related sets of terms.