Where Americans Get and Trust Political Information: Traditional Media Leads, Social Media Grows, AI Emerges

Hwayong Shin | Weidenbaum Center Postdoctoral Fellow in Survey Research

January 16, 2026

Where do Americans turn for political information—and which sources do they actually trust? As traditional news organizations struggle with declining public trust (Brenan 2025; Ladd 2012), social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, X) and artificial intelligence (AI) tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Gemini, Copilot) are increasingly stepping into the information space (Bode 2016; Podimata & Cen 2025). Yet little is known about how these sources compare in citizens’ minds. This question matters because a well-functioning democracy depends not just on the availability of information, but on which sources individuals use and trust to support informed political judgments (Lupia & McCubbins 2019; Soroka & Wlezien 2022).

Long before the rise of social media and AI, political scientists expressed concern about the challenges of cultivating an informed public capable of democratic governance. These concerns have been twofold, focusing on the capacity of both the media and citizens themselves. On the news producer side, the media have long faced skepticism for their role in democracy. Unlike formal political institutions, news organizations lack built-in incentives to serve the public interest and may instead prioritize profit or attention-grabbing content (Hamilton 2004; Patterson 1997). Turning to the audience, citizens have also been viewed with suspicion: many individuals pay little attention to politics (Converse 1964; Lippmann 1925), face cognitive constraints due to limited prior knowledge or everyday pressures (Delli Carpini & Keeter 1996; Lupia & McCubbins 1998), or selectively consume and accept information in ways that reinforce prior beliefs (Taber & Lodge 2006; Zaller 1992). Variations of these concerns have repeatedly surfaced over the past few decades, including debates about partisan media, selective exposure, news avoidance, and political disengagement (Arceneaux et al. 2012; Krupnikov & Ryan 2022; Peterson et al. 2019; Stroud 2010; Toff & Kalogeropoulos 2020)

The rise of social media—and more recently, AI-based tools—has sharpened these long-standing concerns. Social media blurred the boundary between news producers and consumers, weakening professional journalism’s traditional gatekeeping role—the practice through which journalists and editors determine which information becomes news (Soroka & Carbone 2022; Tandoc & Vos 2016). Research also suggests that social media can silo individuals into like-minded “filter bubbles” or “echo chambers,” driven by both individuals’ choices and algorithmic ranking systems (Bakshy et al. 2015; Cinelli et al. 2021). AI tools go one step further by offering personalized, conversational information, potentially reshaping news consumption and introducing new sources of bias (Hu 2025; Motoki et al. 2023). There is even growing public concern that AI may reduce traditional journalism jobs and further harm the quality of news (Lipka 2025).

For some observers, the rise of new sources of political information may signal a threat to journalism’s “fourth estate” role in democracy—its duty “to provide a public forum for debate about the issues of the day; to articulate public opinion and to force governments to consider the will of the people” (Schultz 1998, p. 30)—and raise concerns about the sustainability of traditional news organizations. For others, especially individuals who distrust legacy media, social media and AI tools may represent alternative pathways to political information that bypass traditional news institutions.

Against this backdrop, this article examines patterns of media use and trust using data from the Weidenbaum Center Survey (Wave 7), conducted in October 2025 on a nationally representative sample of Americans (n = 2,954). Four questions are addressed. First, how much do Americans rely on social media and AI chatbots for political information, relative to traditional news media? Second, how does trust in these newer sources compare to trust in traditional media as providers of political information? Third, do patterns of media use and trust diverge across age groups and partisan affiliations—reshaping who gets political news, and how? Finally, to assess the potential political role of AI tools more directly, to what extent do Americans use AI chatbots specifically for political information, as opposed to other purposes?

The results do not necessarily suggest the displacement of traditional news media. Instead, the findings point to a media environment in which newer technologies coexist with—rather than supplant—traditional news outlets as the source of political information for Americans, at least for now.

Where do Americans get and trust political information?

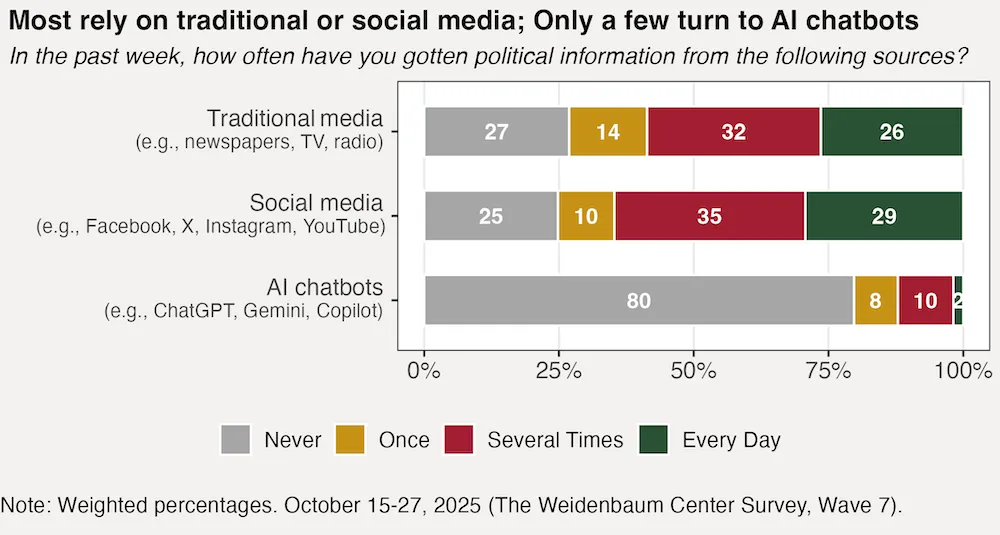

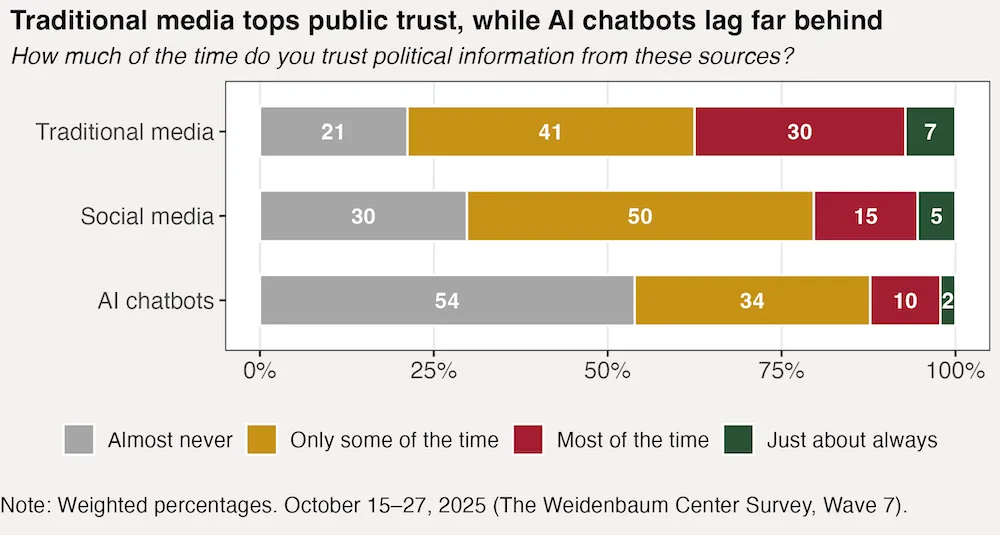

To examine how Americans obtain political information, respondents were asked how often they got political information in the past week from each of the following sources: Traditional media (e.g., newspapers, tv, radio), Social media (e.g., Facebook, X, Instagram, YouTube), and AI chatbots (e.g., ChatGPT, Gemini, Copilot). To assess trust in these sources, respondents were also asked how much of the time they trust political information from each source.

Overall, Americans rely heavily on traditional media and social media, while relatively few turn to AI chatbots for political information. More than seven in ten Americans report using traditional media or social media at least once in the past week to get political information. In contrast, only about two in ten report using AI chatbots for this purpose. This figure is substantially smaller than 57% who report interacting with AI regularly for general purposes in a recent report (McClain et al. 2025), underscoring that the use of AI specifically for political information remains limited.

Patterns of trust across these sources further underscore the central role of traditional media in Americans’ political information environment. Defining trust as reporting that a source is trusted “most of the time” or “just about always,” 37% of Americans express trust in traditional media, compared to 20% for social media and only 12% for AI chatbots. More than half of Americans report that they “almost never” trust AI chatbots as a source of political information, compared to 30% who almost never trust social media and 21% who almost never trust traditional media.

Taken together, these findings suggest that, despite growing concerns that social media and AI tools may overwhelm or supplant traditional news outlets, traditional media remain the most widely used and trusted source of political information among Americans. Social media play an important—but secondary—role, while AI chatbots remain a marginal source of political information, both in terms of use and trust.

Do older and younger Americans diverge in their media use and trust?

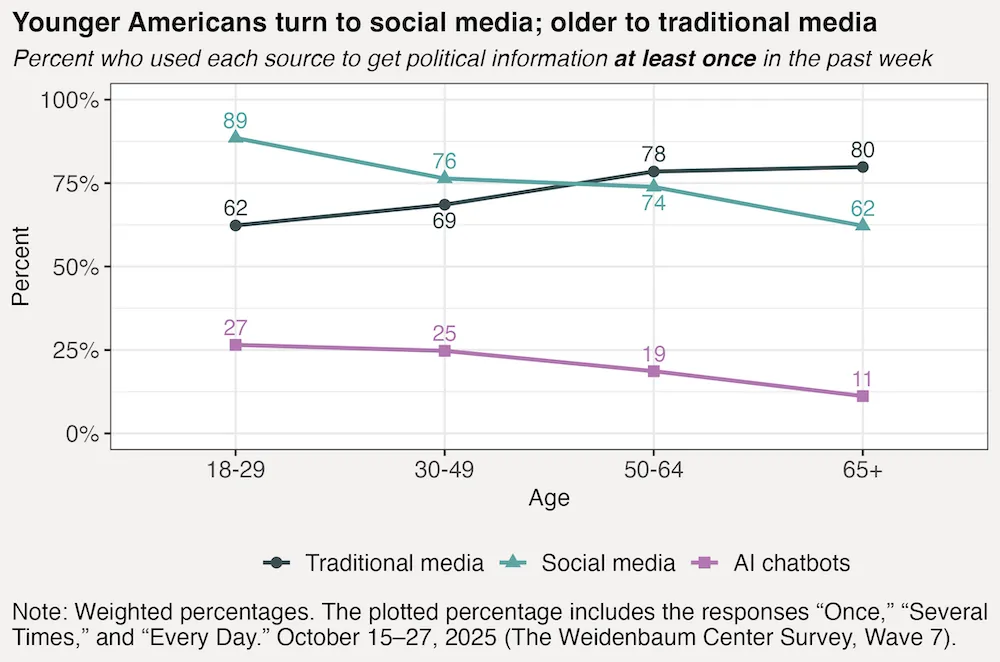

Clear age-based differences emerge in both media use and trust. Older and younger Americans display opposite patterns in their use of traditional and social media. Among adults ages 18–29, only 62% reported using traditional media at least once in the past week for political information, compared to 80% among those ages 65 and older. Social media shows the reverse pattern: 89% of Americans ages 18–29 used social media at least once in the past week for political information, while this share declines to 62% among those ages 65 and older.

AI chatbots remain a relatively marginal source of political information across all age groups. Still, usage is most prevalent among younger Americans: 27% of those ages 18–29 reported using AI chatbots to get political information at least once in the past week, compared to just 11% among those ages 65 and older.

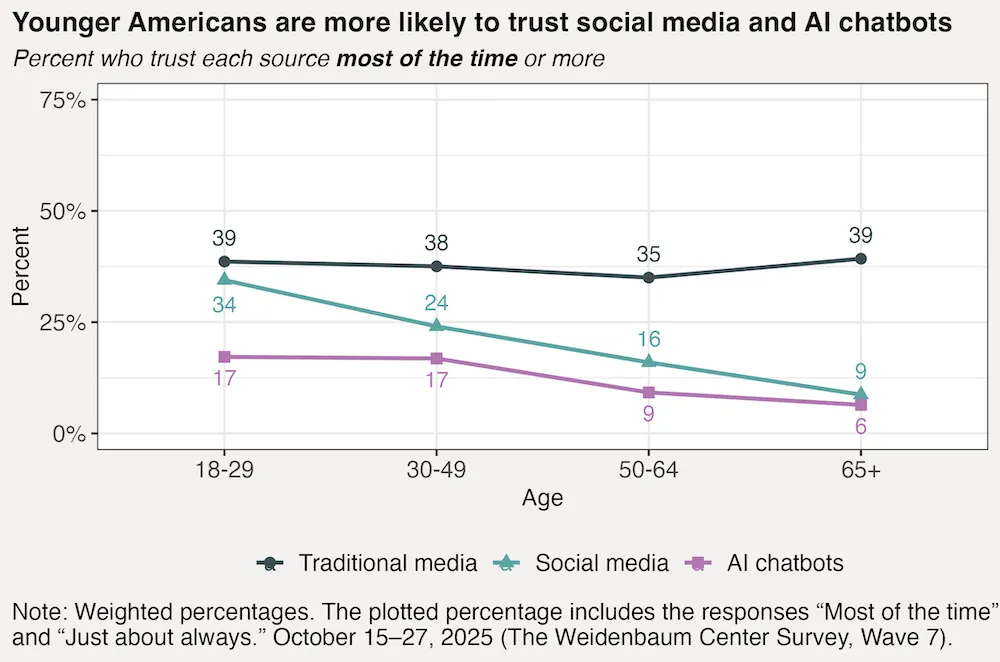

Age differences are more pronounced for some sources than others when it comes to trust. Traditional media exhibits the most stable pattern across generations. Using the same definition of trust as above, roughly four in ten Americans express trust in traditional media across all age groups.

By contrast, trust in social media shows the sharpest generational divide. Among Americans ages 18–29, 34% report trusting social media, but this share drops steeply to 9% among those ages 65 and older. Trust in AI chatbots remains low across all age groups, though it is highest among younger Americans: 17% of those ages 18–29 report trusting AI chatbots, compared to only 6% among those ages 65 and older.

What emerges is a generational pattern: younger and older Americans navigate today’s political information environment differently. The gradual increases and declines in media use and trust across age groups suggest that age plays a meaningful role in shaping how Americans obtain political information and which sources they find credible.

These patterns of media use are largely consistent with recent reports documenting age gaps in traditional and social media consumption in the United States (Gottfried 2024; Randolph & Shearer 2025). The findings on media trust likewise align with recent evidence showing that younger Americans have grown more trusting of social media over time, narrowing the trust gap between social media and legacy news outlets among younger cohorts (Eddy & Shearer 2025).

Does partisanship divide Americans’ media use and trust?

Partisan affiliation is well known to divide Americans’ news consumption and trust, particularly with respect to traditional news media (e.g., Ladd & Podkul 2018). Less is known, however, whether partisan divides extend to newer information sources such as social media and AI tools. The results indicate that partisan gaps remain most pronounced for traditional media, while partisan differences are smaller for social media and nearly nonexistent for AI chatbots.

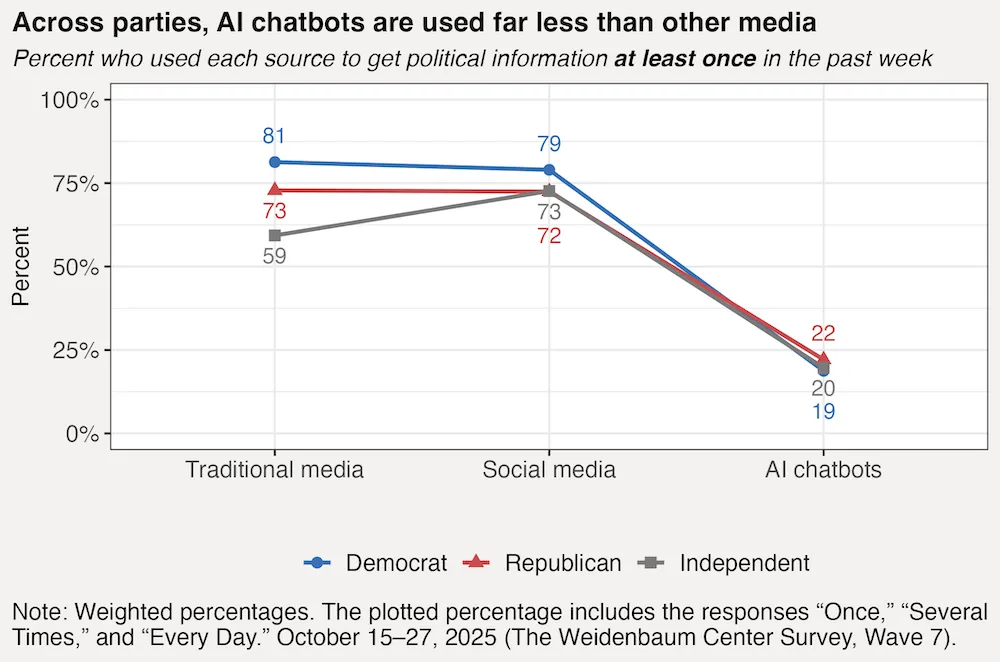

With respect to media use, Democrats were the most frequent users of traditional media: 81% reported using traditional media at least once in the past week. Republicans followed at 73%, while Independents were least likely to rely on traditional media, with only 59% reporting use. Patterns differ for social media. Independents and Republicans reported nearly identical levels of social media use (73% and 72%, respectively), while Democrats again emerged as the most active users, with 79% reporting social media use for political information in the past week.

Use of AI chatbots was low across partisan groups. Even among Democrats—who consistently report higher levels of media usage overall—only 19% used AI chatbots for political information in the past week, compared to 22% of Republicans and 20% of Independents.

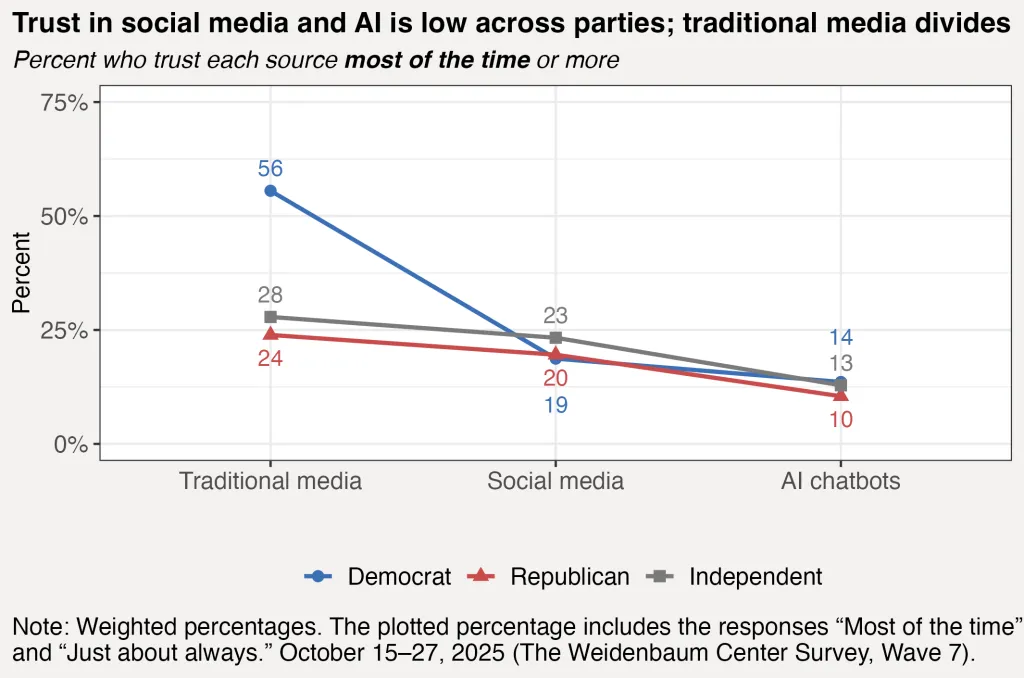

Partisan differences are even more pronounced when it comes to trust in traditional media. More than half of Democrats report trusting traditional media “most of the time” or “just about always,” compared to roughly one in four Republicans. In contrast, trust in social media is uniformly low across parties: approximately two in ten Democrats, Republicans, and Independents report trusting social media as a source of political information. Trust in AI chatbots is lower still, with only about one in ten respondents across partisan groups expressing trust in these tools.

These patterns highlight two notable features of the contemporary media environment. First, partisan divides in media use and trust remain concentrated in traditional media and have not yet fully extended to newer sources such as social media and AI chatbots. Second, media use does not necessarily translate into media trust, and vice versa. For example, while nearly three-quarters of Republicans report using traditional media, their trust in traditional media remains low and comparable to that of Independents, who are substantially less likely to use it. Similarly, although social media is widely used across partisan groups, trust in social media remains limited—suggesting that many Americans consume political information on social platforms with a substantial degree of skepticism.

Are AI chatbots rising as a source of political information?

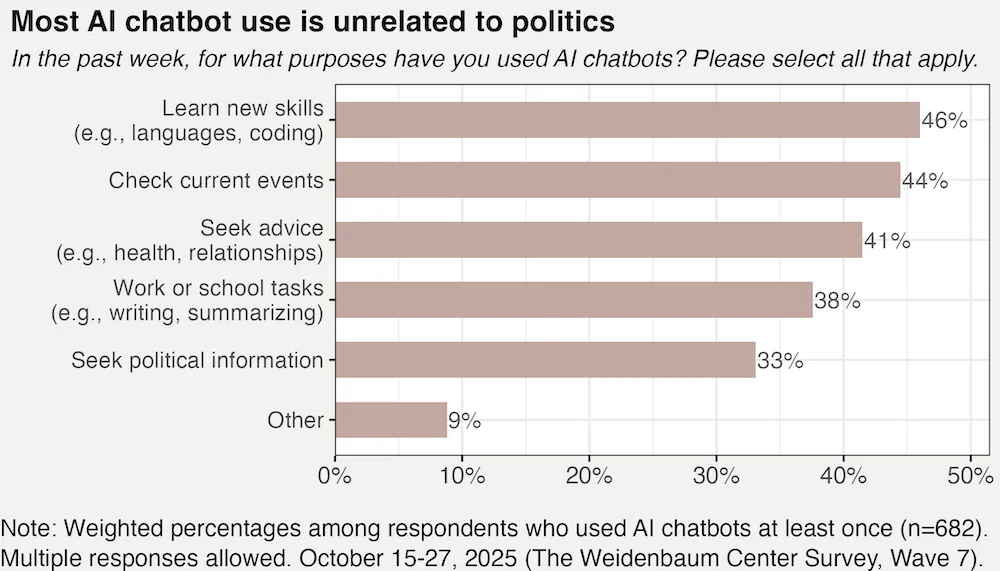

Are concerns about AI chatbots as a new threat to traditional media warranted? To assess the potential role of AI chatbots as a source of political information, respondents who reported having obtained political information from AI chatbots at least once in the past week (n = 682) were asked a follow-up question about the purposes for which they used AI chatbots during that period. Respondents were allowed to select multiple options, including: checking or understanding current events, finding information about politics, getting help with work or school tasks (e.g., writing, summarizing), learning new skills (e.g., languages, coding), seeking advice (e.g., health or personal decisions), and other uses. Importantly, while all respondents in this group had encountered political information through AI chatbots, selecting “finding information about politics” captures those who intentionally used AI chatbots to seek political information, as opposed to those who may have encountered political content incidentally while using AI for other purposes. This distinction can be understood as paralleling the distinction between “actively informed” individuals—those who directly seek out political news—and “casually informed” individuals, who primarily encounter political information through indirect or socially transmitted channels (Carlson 2024, p. 19).

The most common uses of AI chatbots were largely unrelated to politics. Nearly half of users reported using AI chatbots to learn new skills (46%), followed by checking current events (44%), seeking personal advice (41%), and getting help with work or school tasks (38%). By contrast, only about one-third of users (33%) reported using AI chatbots to seek political information.

What this finding suggests is that—even amid growing debates about the political influence of AI chatbots (e.g., Lin et al. 2025; Velez et al. 2025)—their practical role in Americans’ political information environment remains limited, at least for now. When Americans turn to AI chatbots, they are far more likely to use them for everyday, non-political purposes than for learning about politics.

In Closing

The findings from the Weidenbaum Center Survey complicate a long-standing question in political science: can citizens reliably navigate political information in ways that meaningfully inform their judgments? While the current data do not directly assess the quality of news content or the accuracy of citizens’ decisions, they make one point clear—Americans are now embedded in a media environment that is more complex than ever, marked not only by a growing diversity of outlets but also by an expanding range of media forms, including traditional news, social media, and conversational AI.

With this expanding set of choices, Americans increasingly diverge across age groups in how they use and trust different sources, and partisanship further divides which sources individuals find credible. Yet amid this diversification, one pattern stands out: traditional news media continue to command relatively higher levels of trust and stable usage compared to newer platforms. This finding suggests that even as the information landscape evolves, established institutions still play a central role in how citizens orient themselves politically.

Importantly, complexity itself is not new. Nearly a century ago, Walter Lippmann (1922) observed that the world citizens must “deal with politically is out of reach, out of sight, out of mind. It has to be explored, reported, and imagined” (p. 29), highlighting the challenges ordinary citizens face in fully understanding politics. Subsequent scholarship has pushed back against pessimistic concerns about citizens’ capacities. As V.O. Key (1966) put it succinctly, “voters are not fools” (p. 7). For instance, citizens can rely on trusted sources as informational shortcuts to make reasonable judgments (Lupia & McCubbins 1998), and collective public opinion can remain stable and coherent even when individual attitudes fluctuate (Page & Shapiro 1992). From this perspective, lower trust in some media sources may not always signal disengagement, but rather a form of “constructive skepticism”—a healthy response to an increasingly crowded information environment—so long as it remains distinct from “destructive cynicism,” which can obstruct productive exchange of ideas and democratic deliberation (Quiring et al. 2021).

As Delli Carpini and Keeter (1996) remind us, it is still the case that “a central resource for democratic participation is political information” (p. 5). The evidence here suggests that while the diversification of news media may initially challenge citizens, it also holds the potential to equip them—over time—to navigate political information more effectively. In an era of expanding choice, democratic competence may depend not on eliminating complexity, but on how citizens learn to live with it.

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Taylor Carlson and Do Won Kim for their constructive and helpful comments.

Bibliography

Arceneaux, K., Johnson, M., & Murphy, C. (2012). Polarized Political Communication, Oppositional Media Hostility, and Selective Exposure. The Journal of Politics, 74(1), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002238161100123X

Bakshy, E., Messing, S., & Adamic, L. A. (2015). Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science, 348(6239), 1130–1132. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa1160

Bode, L. (2016). Political News in the News Feed: Learning Politics from Social Media. Mass Communication and Society, 19(1), 24–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2015.1045149

Brenan, M. (2024, October 14). Americans’ Trust in Media Remains at Trend Low. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/651977/americans-trust-media-remains-trend-low.aspx

Carlson, T. N. (2024). Through the Grapevine: Socially Transmitted Information and Distorted Democracy. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/T/bo217680791.html

Cinelli, M., De Francisci Morales, G., Galeazzi, A., Quattrociocchi, W., & Starnini, M. (2021). The echo chamber effect on social media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(9), e2023301118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023301118

Converse, P. E. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In D. E. Apter (Ed.), Ideology and Discontent (pp. 206–261). Free Press. https://doi.org/10.1080/08913810608443650

Delli Carpini, M. X., & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans Know about Politics and why it Matters. Yale University Press. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300072754/what-americans-know-about-politics-and-why-it-matters/

Eddy, K., & Shearer, E. (2025, October 29). How Americans’ trust in information from news organizations and social media sites has changed over time. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/10/29/how-americans-trust-in-information-from-news-organizations-and-social-media-sites-has-changed-over-time/

Gans, H. J. (2003). Democracy and the News (120921). Oxford University Press. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=c1afcac0-b8da-336c-80e5-1bb982b23778

Gottfried, J. (2024, January 31). Americans’ Social Media Use. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2024/01/31/americans-social-media-use/

Hamilton, J. T. (2004). All the News That’s Fit to Sell: How the Market Transforms Information into News. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt7smgs

Hu, T., Kyrychenko, Y., Rathje, S., Collier, N., van der Linden, S., & Roozenbeek, J. (2025). Generative language models exhibit social identity biases. Nature Computational Science, 5(1), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-024-00741-1

Key, V. O. Jr. (2013). The Responsible Electorate: Rationality in Presidential Voting, 1936–1960. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674497764

Krupnikov, Y., & Ryan, J. B. (2022). The Other Divide. Cambridge University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108923323

Ladd, J. M. (2012). Why Americans Hate the Media and How It Matters. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt7spr6

Ladd, J. M., & Podkul, A. R. (2018). Distrust of the News Media as a Symptom and a Further Cause of Partisan Polarization. In New Directions in Media and Politics (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203713020-4/distrust-news-media-symptom-cause-partisan-polarization-jonathan-ladd-alexander-podkul

Lin, H., Czarnek, G., Lewis, B., White, J. P., Berinsky, A. J., Costello, T., Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2025). Persuading voters using human–artificial intelligence dialogues. Nature, 648(8093), 394–401. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09771-9

Lipka, M. (2025, April 28). Americans largely foresee AI having negative effects on news, journalists. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/04/28/americans-largely-foresee-ai-having-negative-effects-on-news-journalists/

Lippmann, W. (with Internet Archive). (1922). Public Opinion. Harcourt, Brace. http://archive.org/details/publicopinionhar0000walt

Lippmann, W. (with Internet Archive). (1925). The phantom public. Harcourt, Brace. http://archive.org/details/phantompublic0000walt

Lupia, A., & McCubbins, M. D. (1998). The democratic dilemma: Can citizens learn what they really need to know? Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/us/universitypress/subjects/politics-international-relations/political-economy/democratic-dilemma-can-citizens-learn-what-they-need-know

Lupia, A., & McCubbins, M. D. (2019). Democracy’s Continuing Dilemma: How to Build Credibility in Chaotic Times. PS: Political Science & Politics, 52(4), 654–658. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519000970

Motoki, F., Pinho Neto, V., & Rodrigues, V. (2024). More human than human: Measuring ChatGPT political bias. Public Choice, 198(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01097-2

McClain, C., Kennedy, B., Gottfried, J., Anderson, M., & Pasquini, G. (2025, April 3). Artificial intelligence in daily life: Views and experiences. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2025/04/03/artificial-intelligence-in-daily-life-views-and-experiences/

Page, B. I., & Shapiro, R. Y. (1992). The Rational Public: Fifty Years of Trends in Americans’ Policy Preferences. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/R/bo3762628.html

Patterson, T. E. (1997). The News Media: An Effective Political Actor? Political Communication, 14(4), 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/105846097199245

Peterson, E., Goel, S., & Iyengar, S. (2021). Partisan selective exposure in online news consumption: Evidence from the 2016 presidential campaign. Political Science Research and Methods, 9(2), 242–258. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.55

Podimata, C., & Cen, S. H. (2025, November 21). AI Is Transforming Politics, Much Like Social Media Did. TIME. https://time.com/7334897/how-ai-is-reshaping-politics/

Quiring, O., Ziegele, M., Schemer, C., Jackob, N., Jakobs, I., & Schultz, T. (2021). Constructive Skepticism, Dysfunctional Cynicism? Skepticism and Cynicism Differently Determine Generalized Media Trust. International Journal of Communication, 15, 22–22. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/16127

Randolph, M., & Shearer, E. (2025, August 28). How the audiences of 30 major news sources differ by age. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/08/28/how-the-audiences-of-30-major-news-sources-differ-by-age/

Schultz, J. (1998). Reviving the Fourth Estate: Democracy, Accountability and the Media. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511597138

Soroka, S. N., & Carbone, M. (2022). Gatekeeping, Technology, and Polarization. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.43

Soroka, S. N., & Wlezien, C. (2022). Information and Democracy: Public Policy in the News. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108868242

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 755–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00214.x

Tandoc Jr., E. C., & Vos, T. P. (2016). The Journalist Is Marketing the News: Social media in the gatekeeping process. Journalism Practice, 10(8), 950–966. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1087811

Velez, Y., Green, D., & Sevi, S. (2025). Chatbot-Driven Voting Aid Applications Increase Knowledge about Party Positions but Do Not Change Party Evaluations. APSA Preprints. https://doi.org/10.33774/apsa-2025-s7p22

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511818691

Data

The Weidenbaum Center Survey (WCS), Wave 7 was conducted by Washington University in St. Louis’s Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy through the survey firm YouGov on October 15-27, 2025. The sample included 2,954 respondents. Because there was an oversample of African Americans, the weighted percentages were presented in the results. The number of respondents by partisanship was as follows: Democrats (D) = 1,577, Republicans (R) = 622, Independents (I) = 755 (Wave 1). “Democrats” include individuals identifying as Strong Democrat, Not very strong Democrat, or Lean Democrat; “Republicans” include those identifying as Strong Republican, Not very strong Republican, or Lean Republican; and “Independents” refer to pure independents who identified as Independent without partisan leaning.